Like most runners, Kara Phelps is a planner.

Before leaving his home in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, for May 15 York Roses YMCA Marathon— about an hour and a half away — she made checklists for herself and her two children, aged 10 months and 3 years.

She even called Grace Manor Bed & Breakfast ahead of time to make sure she would have access to a toaster for her pre-race meal. (Otherwise she would have dragged her own – she already did.)

Everything seemed in order when she had put away her clothes and her bib the night before. In the morning, she woke up early, made her toast, and started sipping her coffee.

“That’s when it hit me, before I even got dressed,” said Phelps, 32. The runner’s world. She had forgotten an item from her carefully checked list.

Her shoes – Brooks Glycerins – were home in Lewisburg.

A few tears, phone calls, and pleas to strangers later, she found her knight in shining armor — or, in this case, a nice racing volunteer on an ElliptiGo.

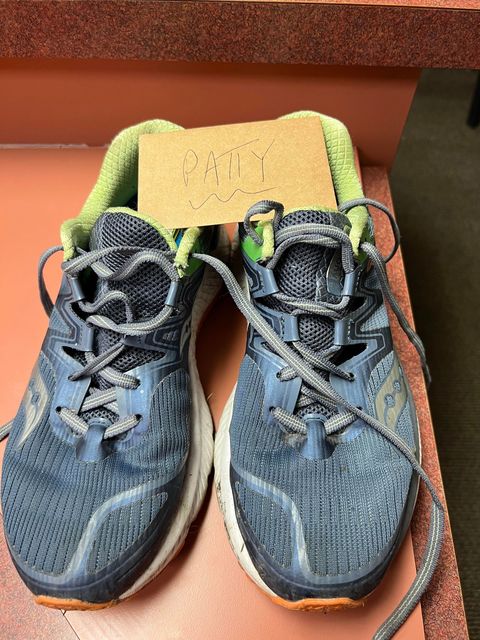

Patti Stirk, 56, lives half a mile from the start of the race. She cycled there to retrieve a pair of Saucony size 8 guides. Phelps put them on and reserved them for her fairy tale end – she won the race in 3:04:15.

the saga highlights the generosity of the running community, the power to ask for help and how resilience and adaptability can help athletes succeed despite the odds, said Hillary Cauthen, Psy.D., Certified Mental Performance Consultant and co-owner of Texas Optimal Performance and Psychological Services in Austin.

Here’s what you can learn from Phelps about handling unexpected issues on race day.

Breathe deeply.

When Phelps realized her oversight, she began to cry, softly at first, to avoid waking her family in the next room. But she knew she needed help, so she woke up her husband, Josh.

He calmed her down and together they went into problem-solving mode. “He was the rock,” she said. “He’s like, ‘We can relate to this.’

Along with Josh’s presence, Phelps’ medical history – she’s a trained nurse at a Level 1 trauma center in the ICU – helped her tap into effective coping techniques, including breathing. deep.

A few slow inhales and exhales can reset your body’s stress response, allowing you to think more clearly, says Stephen Gonzalez, Ph.D.assistant athletic director for leadership and mental performance at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire.

“Taking a few breaths allows you to calm the nervous system,” he said, “to try to create space between what’s happening to you and what you’re going to do.” As Cauthen said, it helps you move from a “what if” mindset to a “what then” mindset.

Look for support.

Josh was already on his team, and Phelps wasn’t shy about reaching out to others. First they called friends, including old neighbors who lived nearby. None wore the correct size (8 to 8.5).

Phelps also called his mother, Kathy Stahl, who was babysitting her dog at their Lewisburg home. Stahl consoled his daughter and offered to drive the shoes off. “Moms are the best,” Phelps said.

But with one eye on the clock—the race started at 6 a.m. and it was around 5:30 a.m.—Phelps decided to head to the York Branch YMCA, where the race began. Maybe there would be shoes in the found, she thought, or another runner with an appropriately sized backup pair.

She started approaching strangers and, after about nine false starts, found Stirk. Not only did she wear the same size and live nearby, but Stirk is also a member of a local racing team sponsored by Flying feet sport – and so, had a ton of trainers to choose from. “I’m like, ‘You’ve come to the right place,'” Stirk said.

Top athletes sometimes find it difficult to ask for help, but connecting to a larger community is key to success, Gonzalez said. On the one hand, others can provide tangible help, like extra shoes in this case.

Plus, feeling supported can ease the emotional burden of obstacles big and small. “Resilience is a team sport,” he said. “The people around you can lift you up and bring you closer to where you were before stress or adversity.”

Channel trust and gratitude.

To stay as calm as possible while she searched for shoes, Phelps recalled all the hard work she put in during training, how she dialed in her sleep and her nutrition during the cut. I’m ready to go now, she thought. “I had this mindset, it has to work.”

The stressful moments that come so soon before a race can bring an adrenaline rush, Cauthen said. Adaptable athletes can quickly channel the energy their running performance brings.

That’s exactly what Phelps did as he raced to the line. Fortunately, the race got off to a flying start; Phelps didn’t start until about five minutes after the shot.

This run was her first backstroke after giving birth, and she wasn’t sure how fast she could run. Based on her training, she thought she could finish in 3:10 – off her personal best of 2:53, but with plenty of cushioning for next spring’s Boston Marathon (her qualifying time is 3:30).

She felt good enough to run a pace of 6:49 per mile during the first half. At mile 20 she hit the wall and her feet started hurting. But seeing Stirk on the course – riding the ElliptiGo, she served as a bike steward – gave Phelps an extra boost.

In difficult times, she adopted a new mantra: “Do it for Patti”. This type of deeper motivation can act as a performance enhancer, Cauthen said: “She had other things to do, which is great.”

Phelps expressed growing gratitude to Stirk, both on the course (at one point, shouting, “your shoes are awesome!”) and after. She left the winning pair at the YMCA for Stirk, along with a thank you note and a gift card to a local restaurant.

Celebrate your resilience and take notes for next time.

After guiding the men’s winner, Cem Aslan, to a finish in 2:45, Stirk turned his ElliptiGo around to ride with Phelps. Although she slowed down, Phelps still beat her showing by over five minutes and second by over six. When she crossed the winning line, Josh and his two children were there to greet her.

Hans Christian Andersen could hardly have written a better ending – and history shows that success is possible, even when the conditions aren’t ideal, Cauthen said.

Of course, not every runner facing a setback on race day will have the same happy outcome forever. Some may need to adjust their goals and expectations, or reach a point where it is wiser to give up than to continue and risk injury. Others may end up missing the chance to compete, no matter how hard they try.

Even if things don’t go as well for you as they did for Phelps, don’t consider your race a failure. Instead, applaud yourself for trying. And know that with every setback comes lessons that can help you perform better next time, whether it’s planning extra time, packing more than you need, or knowing who to call. when needed, Gonzalez said.

Phelps, for her part, said she learned a lot about the value of rolling with the punches. “I think that’s definitely one of the biggest challenges in life, especially as runners,” she said. “We tend to be very controlling. So have faith and know that everything will be fine.

The other good thing about these mishaps? You are unlikely to make the same mistake twice. “I will never forget my sneakers again, I can certainly attest to that,” Phelps said. “I hope to do [the Philadelphia Marathon] this fall, and they will be triple checked.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and uploaded to this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content on piano.io